For decolonized and open access knowledge in South Africa

61- 03/04/ 2023 During the years 2015-2016, South African students representing various movements including RhodesMustFall[1]and FeesMustFall (#FMF) have been fighting for a decolonized and accessible higher education. These social protests faced a double obstacle: the commodification of knowledge and its domination by Northern theorists. In parallel, an Open Access movement is calling for greater visibility for knowledge produced by the South and an alternative to legacy publishers’ profiting from public research through journal subscription fees.

Although they share the same empowerment goals, these two disputes are struggling to come together. Why? Khawulile Radebe, Manager of Scholarly Communications at the University of Pretoria, devotes her master’s thesis presented to the University of Cape Town to exploring a possible interface between these two civic engagements. Her critical analysis contributes to a general awareness of transformations that still need to be carried out so that research and higher education become truly emancipatory and serve development in Africa.

These considerations echo the criticisms of information professionals and those of students and academics who denounce the privileging of colonial and colonialist knowledge in African educational institutions. Explanation…

Decolonizing and democratizing higher education

Empowerment, understood as the power of vulnerable populations to act, is based on the emancipatory practice of education, which carries social transformation (Freire, 1970). To be liberating, education must not perpetuate the shortcomings of colonialism and must be open to all, not only the wealthiest layers of the population. Access to higher education for as many people as possible and the sharing of research results are the pillars of development and social justice. In the Global South, democratization of knowledge is even more crucial as young people rely on postgraduate degrees to overcome past inequalities, eradicate poverty, and improve the social and financial conditions of their communities (Ramrathan, 2016).

In South Africa, during the years 2015 and 2016, these demands were brought to the political stage by a citizen collective of young students that crystallised under the banner of the hashtag #FMF (#FeesMustFall) who railed against colonization of the higher education system and curricula by the Global North, financial exclusion of students, and the slow pace of transformation of universities since 1997, registration fee increases, and continued underdevelopment of historically disadvantaged universities since 1997; the year South Africa adopted its first post-apartheid constitution that made it a constitutionally free and democratic nation… in theory only. In fact, inequalities have persisted. Thus, the decision of the University of Witwatersrand to increase fees by 10.5% sparked outrage in October 2015. Numerous protests and campus occupations followed. The anger spread to other universities such as University of Cape Town, Rhodes University and then to all universities in the country, leading to excesses, on the one hand acts of vandalism and on the other, violent repression … until October 2016[2].

These events caught the attention of Khawulile Radebe a master’s student in the Department of Knowledge & Information Stewardship at the University of Cape Town under the direction of Richard Higgs. She wondered to what extent Open Access[1], a vehicle for democratizing knowledge and promoting social justice, could meet the expectations of #FMF regarding the decolonization and inclusiveness of higher education, Africanization of programs, visibility and accessibility of African and South African content.

According to Khawulile Radebe, Open Access can make a difference.

Open Access is based on two principles :

1- knowledge is a common good that should never be commercialized (Nkoudou and Hervé, 2016)

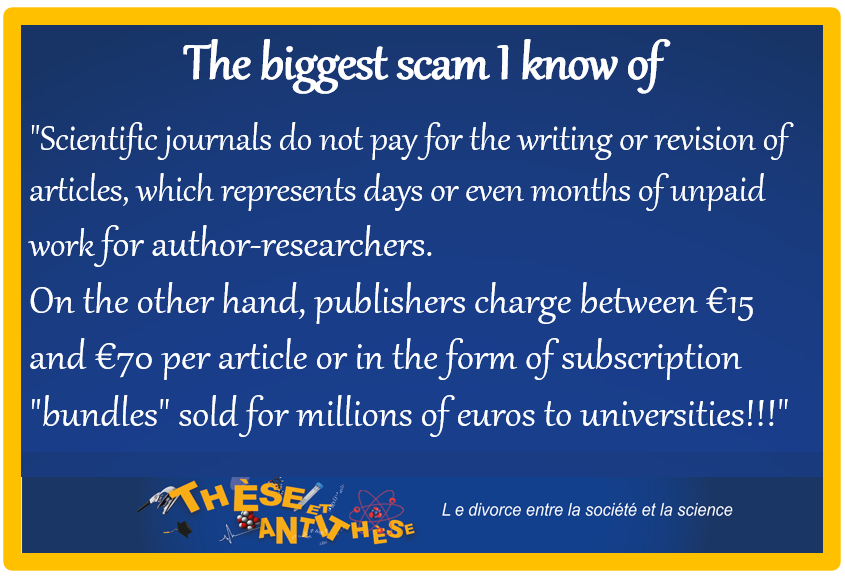

2- publicly funded research should be made available to all, freely, openly and without charge, so that knowledge and innovation can be disseminated as widely as possible. Indeed, the objective of scientific production is to have the greatest impact, not to generate profit (Suber, 2012). Yet the subscription and article purchase fees imposed by journals run counter to this humanistic vision.

How scientific research in Africa is triply penalized

When it comes to access to knowledge and innovation, Africa is subject to a triple penalty. First, because the body of knowledge is dominated by the principles, contexts and theories of the Global North, whereas Southern nations need knowledge designed by and for them to address the challenges that are specific to them. Secondly, due to the scarcity of publications from Southern countries. In Africa, much of grey literature and indigenous knowledge is not published officially and remains hidden.

Finally, because of the prohibitive cost of academic resources. Very expensive compared to the means of African universities and libraries, prohibitive for the poorest, this documentation is outright inaccessible to researchers not affiliated with an organization, who can’t pay for it out of their own pockets.

Unfortunately, universities have become brands that sell themselves at high prices, using marketing related to the ranking of the world’s top universities, research funding, and the number of publications in prestigious journals. So that African universities “are always at the bottom of the ladder, without subscriptions to impact factor journals and without research funding”. Thus, “research is oriented and dictated by foreign funders who prioritize themes that do not always fit with the priorities of the African context. The result is a mismatch between research in Africa and Africa’s needs.” (Nkoudou and Hervé, 2016).

However, Open Access is not a panacea, especially in terms of disseminating African research. Indeed, knowledge from the South does not appear in prestigious international journals indexed by the Web of Science but in local journals with limited dissemination and visibility. It is only by opening up to the products of African research that Open Access will truly reflect the pluralism of viewpoints, languages, concepts and scientific paradigms and improve the quality of scientific information.

Moreover, the Open Access model is not as free as it seems since authors must pay article processing charges to ensure free access to an article. This commodification of knowledge perpetuates inequalities in access to information and the North-South imbalance. Legacy publishers can still profit unfairly from public research by paying lip service to providing Open Access, while forcing researchers to pay to publish. Their tariff barriers prevent the research conducted in less privileged countries and institutions from being known and shared. Hence the crucial importance of removing them.

Despite these limitations, the Open Access approach broadly aligns with the #FMF movement. Both support the decolonizing of knowledge and its free availability, with #FMF calling for the abolition of higher education fees and a vindication of Afrocentric knowledge and Open Access advocating for the removal of publication and subscription fees.

To understand why is it so hard for these two movements to unite their forces, Khawulile Radebe interviewed 12 students, lecturers, researchers and librarians from various universities, namely: Rhodes University, University of Cape Town (UCT) and Nelson Mandela University[5]

Among the main motifs were the lack of visibility of Open Access movement, which not all students know about, and the fact that its model is not totally free. Another less obvious cause, the hidden schism between students and academics/librarians: to put it simply, the #FMF movement brings together students while Open Access appears reserved for academic insiders; a distinction that can generate divisions.

According to Radebe’s Research Director, Richard Higgs of UCT’s Department of Knowledge and Information Stewardship, this schism is indicative of an inadequate commitment to deep transformation by institutions of higher education. The potential of Open Access, despite being aligned with the decolonial goals of student activists, was not mentioned in debates about decoloniality at the time. Many institutionally embedded voices perceived the protestors’ agenda as a threat, rather than an opportunity to find common ground in the interests of knowledge production.. Yet access to free, relevant, and empowering knowledge and research is proving to be beneficial to all. In essence, the failure of some authorities to fully recognize the legitimacy of the student movement was a missed opportunity to simultaneously promote the interests of institutional decolonization and Open Access.

In her summary, Khawulile Radebe calls on higher education institutions to take up the issue of Open Access and Institutional Repositories. Universities have a moral obligation to make research freely available and to ensure that work is included in their repositories. Only research results sharing can boost new knowledge creation. Universities also need to find a balance between incentives to publish in high-impact journals and the benefits of publishing in Open Access journals.

Khawulile Radebe also strongly calls for a more in-depth study on the potential risk of an Open Access being used to spread neocolonialism.

What is the role of academic libraries?

It is up to universities to create an enabling environment, to adopt an empowering organization in terms of support for research and publication for their students. This role could be partly fulfilled by librarians, whose missions could be expanded, for example, to raise students’ awareness of the scientific publication ecosystem in the world, in Africa and South Africa, take a leadership role in drafting OA policies and have them adopted by higher structures, to develop partnerships between university libraries, to share their collections within a virtual library, to seek sponsors…

Rhodes and Mandela’s shadows

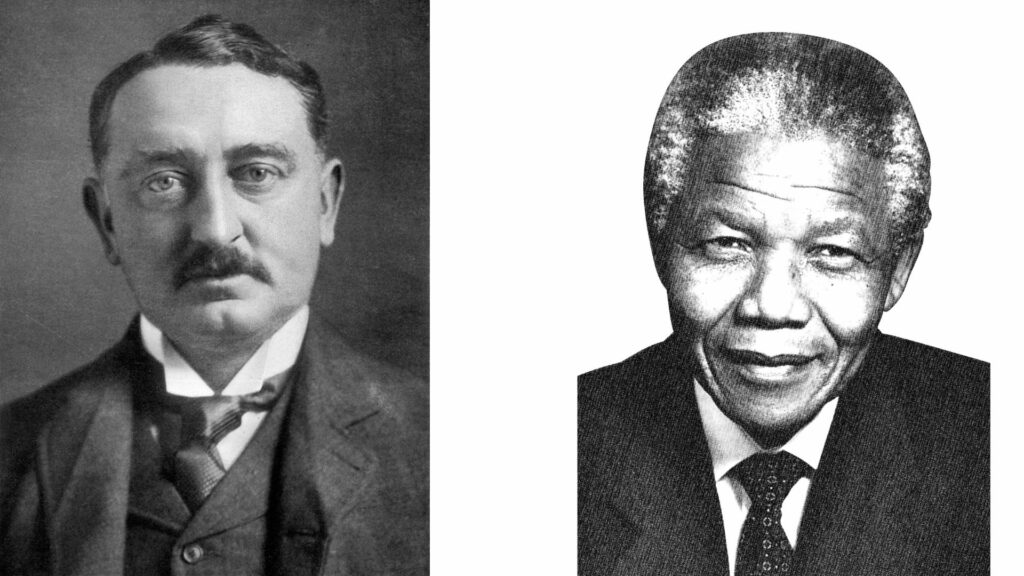

Behind the criticism of science domination by the Global North hover the shadows of Rhodes and Mandela. It is interesting to note that two South African universities bear their names, Rhodes University and Nelson Mandela University, as if the country was still oscillating between an abhorred past but which still weighs on the present, and a future full of promises of social justice and equality but which has difficulty in coming… A perpetual Rhodes Mandela face-off.

As part of the extended decolonization struggle, Rhodes University has come to be known unofficially as UCKAR (The University Currently Known as Rhodes).

| Key figure in South African history, Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902) played a major role in the colonization and territorial expansion of southern Africa. In particular, he founded the British South Africa Company and contributed to the establishment of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and Zambia. Rhodes was a strong supporter of colonialism and British imperialism, and was involved in several controversies related to the exploitation of indigenous workers and land confiscation. His legacy is still much debated in South Africa and around the world.. | Nelson Mandela (1918 – 2013) is considered one of the most important political figures in the history of South Africa and the fight for human rights worldwide. He was imprisoned for 27 years for his opposition to the apartheid regime before becoming the first black president of South Africa in 1994, after negotiating with the government to end apartheid. Mandela was a respected leader for his wisdom, charisma, and commitment to reconciliation and social justice. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 and is often referred to as the ‘father of the South African nation’. |

“Rhodes embodies the dominant mentality that reduces many people to invisibility within a distorted system that seems normal” notes Khawulile Radebe, who later quotes Nelson Mandela, “Education is the most powerful weapon we can use to change the world”. But nothing will change if education remains rooted in colonization, “no generation will free itself from the clutches of the North and our thinking and our minds will remain colonized for years to come” warns Khawulile Radebe.

Open Access science for all non-English speaking countries!

Students from all backgrounds regret that research is subject to big powers and publishers’ greed. For example, European researchers are also subject to American supremacy. Thus, like African languages, European languages are underrepresented and researchers who want to publish in high-impact journals must write in English, the language of science or be translated into it. Results: a weakening of their ideas strength by switching from the mother tongue to English and the impossibility for non-English speaking audiences to access their work 😣!

There are countless forums and posts from angry students against an abstruse but enduring publishing system where public-funded researchers work to write papers, review those of their peers, and ultimately have to pay to publish their research, access it, and read the work of other researchers.

With such processes, society loses part of its investment. As for science, it too loses out depriving itself of public feedback that could open up new perspectives. It misses out on possible collaborations with stakeholders that could lead to other innovations and progress.

Marie-Georges Fayn, Khawulile Radebe*, Richard Higgs**

* Author of the Master’s thesis “Exploring the interface between decolonization of higher education and Open Access” Khawulile Radebe holds the position of Manager: Scholarly Communications at the University of Pretoria – South Africa

**Khawulile Radebe’s Research Director, Richard Higgs is a lecturer in the Department of Knowledge and Information Stewardship at the University of Cape Town – South Africa

*** https://www.linkedin.com/posts/marie-georges-fayn-phd-1a6b2228_revues-doctorants-chercheurs-activity-6795941697713967104-wBoi?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop

Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities encourage researchers/grant recipients to publish their work according to the principles of the open access paradigm and institution to provide them resources on the Internet. (22 October 2003). In order to realize the vision of a global and accessible representation of knowledge, the future Web has to be sustainable, interactive, and transparent. Content and software tools must be openly accessible and compatible.

Bibliographie

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (MB Ramos, Trans.). New York: Continuum, 2007.

Khawulile Ednah Radebe (2022) Exploring the Interface between the Decolonisation of Higher Education and Open Access – Master these of Library and Information Studies, Department of Knowledge and Information Stewardship, Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town

https://open.uct.ac.za/handle/11427/36919

Nkoudou, M. and Hervé, T. 2016. Cognitive injustices in sub-Saharan Africa: reflections on causes and means. In Cognitive justice, open access and local knowledge: for a fair open science, at the service of sustainable local development, under the direction of Florence Piron, Samuel Regulus and Marie Sophie Dibounje Madiba. Quebec.

Ramrathan, L. 2016. Beyond counting the numbers: shifting higher education transformation into curriculum spaces. Transformation in Higher Education. 1(1): 1-8.

Suber, P. (2012). Open access (p. 256). The MIT Press. series. Cambridge

[1] RhodesMustFall (Rhodes must fall) is a protest movement that began in 2015 in South Africa, calling for the removal of the statue of British tycoon and politician Cecil Rhodes erected on the University of Cape Town campus. The movement aimed to challenge institutionalized racism and promote decolonization in education. It sparked similar protests around the world, leading to the removal of other controversial statues and monuments.

[2] The movement ran out of steam at the end of 2016 after obtaining major advances such as an increased budget dedicated to higher education of 17 billion Rand (860 million euros) over 3 years and an increase of 10.9% per year in government subsidies allocated to universities. Another step forward is the development of blended learning (the expansion of online courses). As for tuition fees, they have been increased, but to a lesser extent, 8% instead of the 10% planned for the University of the Witwatersrand

[3] Open access is defined as a comprehensive source of human knowledge and cultural heritage that has been approved by the scientific community.

[4] Source WoS cité dans CNRS PLAN PLURIANNUEL DE COOPÉRATIONS DU CNRS AVEC L’AFRIQUE P11 https://www.cnrs.fr/sites/default/files/page/2022-01/Plaquette_Afrique_web.pdf

[5] Guiding Questions: 1. What is your understanding of the objectives of Open Access? – 2. How do you see the objectives Open Access aligning with those of #FMF movement and decolonisation? – 3. Why do you think there hasn’t been a closer alignment of the objectives of Open Access and of #FMF movement? -4. What do you think are the challenges facing Open Access publishing model in South Africa and how do you think those relate to decolonisation? -5. Do you think Open Access can contribute to increasing the visibility/availability of African research content? If Yes/No, why ?